Listen to the Birdsong: Finding Stillness and Hope in the Noise

Listen to the Birdsong: Finding Stillness and Hope in the Noise

Listen to the Birdsong: Finding Stillness and Hope in the Noise

YouTube video highlight

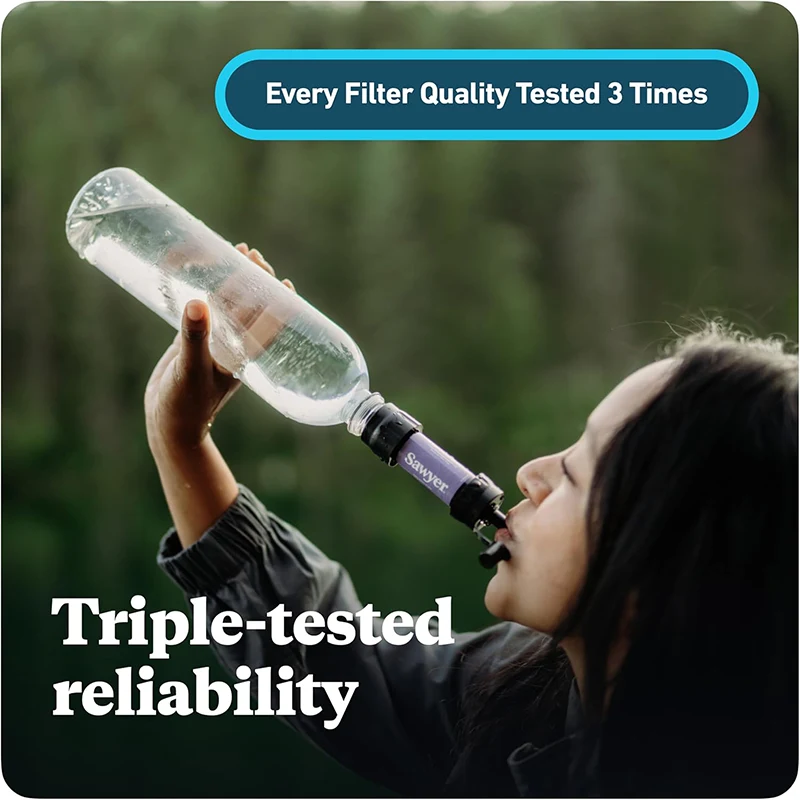

Words and photos by Sawyer Ambassador Amiththan 'Bittergoat' Sebarajah

Read more about the project

Words and photos by Sawyer Ambassador Amiththan 'Bittergoat' Sebarajah

Kati te hoe, eh, mate. Kati te hoe, his gentle voice nudges me from behind, over the mellifluous slap of the river against our waka. I cease paddling furiously and place the oar back into the canoe; the waka glides along a deep and steady current, transporting the two of us according to its own timeless flow; as it has always done.

As part of the Whanganui River segment of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Te Araroa, I had unwittingly ended up on a sacred Maori pilgrimage restricted to outsiders.

Whakarongo ki te waiata, he says as we drift along the wide channel between the steep, verdant canyon walls--the perfect amphitheater for the rich and varied symphony of birdsong reverberating all around me.

Just close your eyes and listen to the song. I’ll steer the waka. Relax and listen for a minute. Ka Pai?!

And I do.

I give into the raucous noise until I begin to notice individual notes of the ensemble.

At first, I was surprised to register the birdsong. How could I have been so oblivious to this music? Moments before I had focused all my energy into the paddle. I could hear the swish and swirl of the water well enough, and my eyes took careful note of the eddies and the sudsy ripples that mark the confluence of subaqueous storylines--in case I had to adjust course in a hurry. I was intent on staying afloat, to not capsize our waka.

My grandfather was a canoe-maker, but I am uncomfortable around water. I’ve never sat in one of his canoes. Nor had I any realistic hope of paddling one of his craft along the crocodile-infested waters of a brackish lagoon that bordered the ocean and the village where I was born. My mother simply gave no quarter to my boyish desires to be out there. Snakes and sea crocodiles aside, she had to consider the army camps and rebel holdouts among the mangrove forests that lined its banks. She wouldn’t chance my life on those troubled waters.

Prior to the 2004 tsunami which decimated the coast and changed the geography of our beaches, the pitiless undertow of the Indian ocean was no place for a careless frolic. Even before the tsunami the ocean gave and claimed with benign indifference.

On an island, surrounded by two massive and foreboding bodies of water I grew up without knowing how to swim. I still carry that mental block even though I am perfectly capable of the physical act.

Before I climbed aboard the canoe with my komatua, I remember asking my grandfather to watch over me on the water. I had never done that type of prayer before but it felt surreal and necessary. I was sure I’d capsize. I desperately wanted to prove to a people for whom the Whanganui River is Tupuna that my ancestors too are a people of the water; that I belonged in this space regardless of my abilities and anxieties. So I was hellbent on staying afloat; I had to block everything else out. And in the process, I almost risked missing a salient point of being on that waterborne section of my thru-hike.

The flora along the Whanganui river retain their natural mystique for me even today. So too the fauna, especially the bird folk of New Zealand, many of whom are flightless and are unique to that living landscape.

That moment with the Nga Manu-- our bird relatives-- on the river would redefine my approach to thru-hiking and refine the way in which I have since strived to relate to the land and to myself.

Had I been on a different course, the 120 km paddle may have taken considerably less time to negotiate. And it would have been adventurous and challenging in another way. However, my time with the komatua and the awa made it possible for me to slow down and listen to the currents of the river curl and dissolve, to the ancient cry of piwakawaka the fantail, the full throaty trill of Tui and the muffled huff and puff of kereru the wood pigeon taking flight. Over the course of twelve days, the river, the people, and the birds taught me a secret as old as time: the land wields power and has a language for those who would listen; against the backdrop of which we learn ourselves and our place in this world.

Ojibway writer Richard Wagamese articulates this point again and again in his novels, especially his most recent and final work Starlight.

‘There’s great love out there. I know that better’n most because it was the land that was my mother all my life and it always will be. That might sound Indian. I don’t know. All’s I know is that it sounds like me. My truth. What I carry around inside my belly now instead of lonesome. Lately, I’m comin’ to know more of love and I sorta think it ain't no great mystery at all when ya look for the core of it, and that core is that loving something or someone is you allowing it or them to lead ya back to who you really are.’ - (Frank Starlight)

These days I find myself reflecting back on what it means to slow down and be still, especially at a moment in my life--indeed in many of our lives--there seems to be so little choice in the matter.

I feel like I have been again paddling furiously just to stay afloat and have forgotten to listen to the birds in the struggle.

These days I find myself at a quiet place in the mountainous hinterlands of British Columbia. Behind our home is a wild river, a major spawning ground for landlocked kokanee salmon. Our infrequent visitors include an itinerant doe and her fawn, an energetic pine marten, and an unseen and solitary bobcat who leaves behind only her hallowed footprints in the snow.

I find myself at a place I did not anticipate. I’m sure that this sentiment is resonant and that in this way I am not alone. The sadness and the irony of this shared and disconnected reality is not lost on me either. Even with hindsight, I could not have predicted a year like this one five years ago. I once had employment to which I was returning; had made plans to see friends and family, to walk long distances slowly, deliberately, without defined goals or agenda.

And now I have the birds and their once timely and always timeless lessons. It happened quite by accident when I had agreed to participate in an annual winter bird count that takes place in this community. Until then, I had relegated birdwatching to the same perch as expensive lattes--an activity reserved for the affluent and the settled. Luckily, I was wrong.

Seven years ago, on a cold and clear winter day, I set out for the first time to look for birds with any sort of intention. My companion was the consummate portrait of a mountain hermit; he wore a grizzled and wirey comportment won over a lifetime spent mostly alone and in wild places. His jeans were tattered, his boots sturdy. He had eyesight that outshone his seven decades of existence. He lived alone and loved the birds. Mostly, he loved the land and the magnitude of its feigned silence that spoke in so many voices, if one but slowed down enough to listen. Later that year I would decide to walk the Appalachian trail, my first multi-day hike of any distance.

That day we counted American Dippers, Winter and Marsh Wrens, numerous species of waterfowl, brightly plumed Stellar Jays, greyish Canada Jays, finches of all types, sparrows, chickadees and song birds, methodic woodpeckers and the carnivorous, crimson-tinged Northern Flickers.

That day I learned their names. That day, I heard their call, but until that day, I had not noticed that they were there all along. I simply hadn’t looked.

Joe Harkness knows this well. Bird watching, for him, was a way towards being more mindful, about establishing a connection to himself through the birds. It opened up my eyes, he says, to what I was doing when I was outside and at this point I started bird watching and it all sort of clicked into place and it became my therapy, my bird therapy. Harkness went on to blog about his experience and eventually published Bird Therapy: On The Healing Effects of Watching Birds. He watched birds and wrote his way towards reestablishing a connection to himself through the natural world from a very bleak place. You can listen to him speak about his experiences here.

GrrlScientist the science writer and ornithologist who profiled Harkness for Forbes Magazine agrees. She writes:

Although I’m a lifelong birder, I was particularly interested to learn how birding develops mindfulness. Birding is a meditative practice that immediately appeals to all your senses listening to bird sounds and songs, looking at their plumage colors and patterns, observing their complex and often subtle behaviors, identifying their habits and habitats but weirdly, I’d not made this connection between birding and mindfulness before.

In the past seven years, I had to slow down intentionally. With each step, I get slower, but somehow always find myself farther along. I am learning to carry the weight of childhood trauma: of war, of dislocation, of growing up, of being a conscientious member of the human species on this planet. I cannot say that it gets lighter but I am constantly learning myself against the context of the land and the contested places I occupy and share with other beings. I have come to find my stillness in movement.

Over the course of this Autumn, the eagles have been patrolling the river, hoping for spent and tired salmon swimming against the current. Each morning I wake up, look out the window and I see the eagle, sitting, waiting, hoping. I try to emulate her, push my ears out to listen to her shrill calls; imperceptible at first, camouflaged within the ambient noise and the chatter in my head--Then I hear it, make out her high pitched giggle: it is barely a whimper, sweet and melodic; and delightfully at odds with such a powerful creature.

I observe her stillness closely, tune my ears a bit sharper. I realize again that the eagle is teaching me something.

But it isn’t the eagle, not really. It is me. I am the stillness and the stillness is in me.

To Hope:

The salmon have moved on,

Having met, mated, given, and given up life;

Leaves on the Apple cling on,

though the birch is bare: tendrils in mist, asking questions, ashen white.

The bears too have gone to dream, dreaming their wintry dreams.

Yet she, sharp-eyed and whiteplumed,

Returns to this tree--her stalwart cottonwood.

Day after day,

Year after year.

Resources:

Crisis Centers Canada

USA Crisis Helplines

Bird songs and Calls of New Zealand

Cornell Lab of Ornithology (North American Bird Song registry)

Suggested Readings:

Wagamese, Richard. Medicine Walk , Starlight

Rorher, Finlo : Slow Death of Purposeless Walking

Harkness, Joe: Bird Therapy: On the Healing Effects of Watching Birds

Adams, Jill.U : How to Boost Your Empathy and Mindfulness While Birding

Birding With Benefits: How Nature Improves Our Mental Mindsets

Mock, Jillian : Black Birders Week Promotes Diversity and Takes on Racism in the Outdoors

Langin, Katie: ‘I can’t even enjoy this:’ #BlackBirdersWeek Organizer Shares Her Struggles

Listen to the Birdsong: Finding Stillness and Hope in the Noise

Words and photos by Sawyer Ambassador Amiththan 'Bittergoat' Sebarajah

Kati te hoe, eh, mate. Kati te hoe, his gentle voice nudges me from behind, over the mellifluous slap of the river against our waka. I cease paddling furiously and place the oar back into the canoe; the waka glides along a deep and steady current, transporting the two of us according to its own timeless flow; as it has always done.

As part of the Whanganui River segment of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Te Araroa, I had unwittingly ended up on a sacred Maori pilgrimage restricted to outsiders.

Whakarongo ki te waiata, he says as we drift along the wide channel between the steep, verdant canyon walls--the perfect amphitheater for the rich and varied symphony of birdsong reverberating all around me.

Just close your eyes and listen to the song. I’ll steer the waka. Relax and listen for a minute. Ka Pai?!

And I do.

I give into the raucous noise until I begin to notice individual notes of the ensemble.

At first, I was surprised to register the birdsong. How could I have been so oblivious to this music? Moments before I had focused all my energy into the paddle. I could hear the swish and swirl of the water well enough, and my eyes took careful note of the eddies and the sudsy ripples that mark the confluence of subaqueous storylines--in case I had to adjust course in a hurry. I was intent on staying afloat, to not capsize our waka.

My grandfather was a canoe-maker, but I am uncomfortable around water. I’ve never sat in one of his canoes. Nor had I any realistic hope of paddling one of his craft along the crocodile-infested waters of a brackish lagoon that bordered the ocean and the village where I was born. My mother simply gave no quarter to my boyish desires to be out there. Snakes and sea crocodiles aside, she had to consider the army camps and rebel holdouts among the mangrove forests that lined its banks. She wouldn’t chance my life on those troubled waters.

Prior to the 2004 tsunami which decimated the coast and changed the geography of our beaches, the pitiless undertow of the Indian ocean was no place for a careless frolic. Even before the tsunami the ocean gave and claimed with benign indifference.

On an island, surrounded by two massive and foreboding bodies of water I grew up without knowing how to swim. I still carry that mental block even though I am perfectly capable of the physical act.

Before I climbed aboard the canoe with my komatua, I remember asking my grandfather to watch over me on the water. I had never done that type of prayer before but it felt surreal and necessary. I was sure I’d capsize. I desperately wanted to prove to a people for whom the Whanganui River is Tupuna that my ancestors too are a people of the water; that I belonged in this space regardless of my abilities and anxieties. So I was hellbent on staying afloat; I had to block everything else out. And in the process, I almost risked missing a salient point of being on that waterborne section of my thru-hike.

The flora along the Whanganui river retain their natural mystique for me even today. So too the fauna, especially the bird folk of New Zealand, many of whom are flightless and are unique to that living landscape.

That moment with the Nga Manu-- our bird relatives-- on the river would redefine my approach to thru-hiking and refine the way in which I have since strived to relate to the land and to myself.

Had I been on a different course, the 120 km paddle may have taken considerably less time to negotiate. And it would have been adventurous and challenging in another way. However, my time with the komatua and the awa made it possible for me to slow down and listen to the currents of the river curl and dissolve, to the ancient cry of piwakawaka the fantail, the full throaty trill of Tui and the muffled huff and puff of kereru the wood pigeon taking flight. Over the course of twelve days, the river, the people, and the birds taught me a secret as old as time: the land wields power and has a language for those who would listen; against the backdrop of which we learn ourselves and our place in this world.

Ojibway writer Richard Wagamese articulates this point again and again in his novels, especially his most recent and final work Starlight.

‘There’s great love out there. I know that better’n most because it was the land that was my mother all my life and it always will be. That might sound Indian. I don’t know. All’s I know is that it sounds like me. My truth. What I carry around inside my belly now instead of lonesome. Lately, I’m comin’ to know more of love and I sorta think it ain't no great mystery at all when ya look for the core of it, and that core is that loving something or someone is you allowing it or them to lead ya back to who you really are.’ - (Frank Starlight)

These days I find myself reflecting back on what it means to slow down and be still, especially at a moment in my life--indeed in many of our lives--there seems to be so little choice in the matter.

I feel like I have been again paddling furiously just to stay afloat and have forgotten to listen to the birds in the struggle.

These days I find myself at a quiet place in the mountainous hinterlands of British Columbia. Behind our home is a wild river, a major spawning ground for landlocked kokanee salmon. Our infrequent visitors include an itinerant doe and her fawn, an energetic pine marten, and an unseen and solitary bobcat who leaves behind only her hallowed footprints in the snow.

I find myself at a place I did not anticipate. I’m sure that this sentiment is resonant and that in this way I am not alone. The sadness and the irony of this shared and disconnected reality is not lost on me either. Even with hindsight, I could not have predicted a year like this one five years ago. I once had employment to which I was returning; had made plans to see friends and family, to walk long distances slowly, deliberately, without defined goals or agenda.

And now I have the birds and their once timely and always timeless lessons. It happened quite by accident when I had agreed to participate in an annual winter bird count that takes place in this community. Until then, I had relegated birdwatching to the same perch as expensive lattes--an activity reserved for the affluent and the settled. Luckily, I was wrong.

Seven years ago, on a cold and clear winter day, I set out for the first time to look for birds with any sort of intention. My companion was the consummate portrait of a mountain hermit; he wore a grizzled and wirey comportment won over a lifetime spent mostly alone and in wild places. His jeans were tattered, his boots sturdy. He had eyesight that outshone his seven decades of existence. He lived alone and loved the birds. Mostly, he loved the land and the magnitude of its feigned silence that spoke in so many voices, if one but slowed down enough to listen. Later that year I would decide to walk the Appalachian trail, my first multi-day hike of any distance.

That day we counted American Dippers, Winter and Marsh Wrens, numerous species of waterfowl, brightly plumed Stellar Jays, greyish Canada Jays, finches of all types, sparrows, chickadees and song birds, methodic woodpeckers and the carnivorous, crimson-tinged Northern Flickers.

That day I learned their names. That day, I heard their call, but until that day, I had not noticed that they were there all along. I simply hadn’t looked.

Joe Harkness knows this well. Bird watching, for him, was a way towards being more mindful, about establishing a connection to himself through the birds. It opened up my eyes, he says, to what I was doing when I was outside and at this point I started bird watching and it all sort of clicked into place and it became my therapy, my bird therapy. Harkness went on to blog about his experience and eventually published Bird Therapy: On The Healing Effects of Watching Birds. He watched birds and wrote his way towards reestablishing a connection to himself through the natural world from a very bleak place. You can listen to him speak about his experiences here.

GrrlScientist the science writer and ornithologist who profiled Harkness for Forbes Magazine agrees. She writes:

Although I’m a lifelong birder, I was particularly interested to learn how birding develops mindfulness. Birding is a meditative practice that immediately appeals to all your senses listening to bird sounds and songs, looking at their plumage colors and patterns, observing their complex and often subtle behaviors, identifying their habits and habitats but weirdly, I’d not made this connection between birding and mindfulness before.

In the past seven years, I had to slow down intentionally. With each step, I get slower, but somehow always find myself farther along. I am learning to carry the weight of childhood trauma: of war, of dislocation, of growing up, of being a conscientious member of the human species on this planet. I cannot say that it gets lighter but I am constantly learning myself against the context of the land and the contested places I occupy and share with other beings. I have come to find my stillness in movement.

Over the course of this Autumn, the eagles have been patrolling the river, hoping for spent and tired salmon swimming against the current. Each morning I wake up, look out the window and I see the eagle, sitting, waiting, hoping. I try to emulate her, push my ears out to listen to her shrill calls; imperceptible at first, camouflaged within the ambient noise and the chatter in my head--Then I hear it, make out her high pitched giggle: it is barely a whimper, sweet and melodic; and delightfully at odds with such a powerful creature.

I observe her stillness closely, tune my ears a bit sharper. I realize again that the eagle is teaching me something.

But it isn’t the eagle, not really. It is me. I am the stillness and the stillness is in me.

To Hope:

The salmon have moved on,

Having met, mated, given, and given up life;

Leaves on the Apple cling on,

though the birch is bare: tendrils in mist, asking questions, ashen white.

The bears too have gone to dream, dreaming their wintry dreams.

Yet she, sharp-eyed and whiteplumed,

Returns to this tree--her stalwart cottonwood.

Day after day,

Year after year.

Resources:

Crisis Centers Canada

USA Crisis Helplines

Bird songs and Calls of New Zealand

Cornell Lab of Ornithology (North American Bird Song registry)

Suggested Readings:

Wagamese, Richard. Medicine Walk , Starlight

Rorher, Finlo : Slow Death of Purposeless Walking

Harkness, Joe: Bird Therapy: On the Healing Effects of Watching Birds

Adams, Jill.U : How to Boost Your Empathy and Mindfulness While Birding

Birding With Benefits: How Nature Improves Our Mental Mindsets

Mock, Jillian : Black Birders Week Promotes Diversity and Takes on Racism in the Outdoors

Langin, Katie: ‘I can’t even enjoy this:’ #BlackBirdersWeek Organizer Shares Her Struggles

Listen to the Birdsong: Finding Stillness and Hope in the Noise

Words and photos by Sawyer Ambassador Amiththan 'Bittergoat' Sebarajah

Kati te hoe, eh, mate. Kati te hoe, his gentle voice nudges me from behind, over the mellifluous slap of the river against our waka. I cease paddling furiously and place the oar back into the canoe; the waka glides along a deep and steady current, transporting the two of us according to its own timeless flow; as it has always done.

As part of the Whanganui River segment of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Te Araroa, I had unwittingly ended up on a sacred Maori pilgrimage restricted to outsiders.

Whakarongo ki te waiata, he says as we drift along the wide channel between the steep, verdant canyon walls--the perfect amphitheater for the rich and varied symphony of birdsong reverberating all around me.

Just close your eyes and listen to the song. I’ll steer the waka. Relax and listen for a minute. Ka Pai?!

And I do.

I give into the raucous noise until I begin to notice individual notes of the ensemble.

At first, I was surprised to register the birdsong. How could I have been so oblivious to this music? Moments before I had focused all my energy into the paddle. I could hear the swish and swirl of the water well enough, and my eyes took careful note of the eddies and the sudsy ripples that mark the confluence of subaqueous storylines--in case I had to adjust course in a hurry. I was intent on staying afloat, to not capsize our waka.

My grandfather was a canoe-maker, but I am uncomfortable around water. I’ve never sat in one of his canoes. Nor had I any realistic hope of paddling one of his craft along the crocodile-infested waters of a brackish lagoon that bordered the ocean and the village where I was born. My mother simply gave no quarter to my boyish desires to be out there. Snakes and sea crocodiles aside, she had to consider the army camps and rebel holdouts among the mangrove forests that lined its banks. She wouldn’t chance my life on those troubled waters.

Prior to the 2004 tsunami which decimated the coast and changed the geography of our beaches, the pitiless undertow of the Indian ocean was no place for a careless frolic. Even before the tsunami the ocean gave and claimed with benign indifference.

On an island, surrounded by two massive and foreboding bodies of water I grew up without knowing how to swim. I still carry that mental block even though I am perfectly capable of the physical act.

Before I climbed aboard the canoe with my komatua, I remember asking my grandfather to watch over me on the water. I had never done that type of prayer before but it felt surreal and necessary. I was sure I’d capsize. I desperately wanted to prove to a people for whom the Whanganui River is Tupuna that my ancestors too are a people of the water; that I belonged in this space regardless of my abilities and anxieties. So I was hellbent on staying afloat; I had to block everything else out. And in the process, I almost risked missing a salient point of being on that waterborne section of my thru-hike.

The flora along the Whanganui river retain their natural mystique for me even today. So too the fauna, especially the bird folk of New Zealand, many of whom are flightless and are unique to that living landscape.

That moment with the Nga Manu-- our bird relatives-- on the river would redefine my approach to thru-hiking and refine the way in which I have since strived to relate to the land and to myself.

Had I been on a different course, the 120 km paddle may have taken considerably less time to negotiate. And it would have been adventurous and challenging in another way. However, my time with the komatua and the awa made it possible for me to slow down and listen to the currents of the river curl and dissolve, to the ancient cry of piwakawaka the fantail, the full throaty trill of Tui and the muffled huff and puff of kereru the wood pigeon taking flight. Over the course of twelve days, the river, the people, and the birds taught me a secret as old as time: the land wields power and has a language for those who would listen; against the backdrop of which we learn ourselves and our place in this world.

Ojibway writer Richard Wagamese articulates this point again and again in his novels, especially his most recent and final work Starlight.

‘There’s great love out there. I know that better’n most because it was the land that was my mother all my life and it always will be. That might sound Indian. I don’t know. All’s I know is that it sounds like me. My truth. What I carry around inside my belly now instead of lonesome. Lately, I’m comin’ to know more of love and I sorta think it ain't no great mystery at all when ya look for the core of it, and that core is that loving something or someone is you allowing it or them to lead ya back to who you really are.’ - (Frank Starlight)

These days I find myself reflecting back on what it means to slow down and be still, especially at a moment in my life--indeed in many of our lives--there seems to be so little choice in the matter.

I feel like I have been again paddling furiously just to stay afloat and have forgotten to listen to the birds in the struggle.

These days I find myself at a quiet place in the mountainous hinterlands of British Columbia. Behind our home is a wild river, a major spawning ground for landlocked kokanee salmon. Our infrequent visitors include an itinerant doe and her fawn, an energetic pine marten, and an unseen and solitary bobcat who leaves behind only her hallowed footprints in the snow.

I find myself at a place I did not anticipate. I’m sure that this sentiment is resonant and that in this way I am not alone. The sadness and the irony of this shared and disconnected reality is not lost on me either. Even with hindsight, I could not have predicted a year like this one five years ago. I once had employment to which I was returning; had made plans to see friends and family, to walk long distances slowly, deliberately, without defined goals or agenda.

And now I have the birds and their once timely and always timeless lessons. It happened quite by accident when I had agreed to participate in an annual winter bird count that takes place in this community. Until then, I had relegated birdwatching to the same perch as expensive lattes--an activity reserved for the affluent and the settled. Luckily, I was wrong.

Seven years ago, on a cold and clear winter day, I set out for the first time to look for birds with any sort of intention. My companion was the consummate portrait of a mountain hermit; he wore a grizzled and wirey comportment won over a lifetime spent mostly alone and in wild places. His jeans were tattered, his boots sturdy. He had eyesight that outshone his seven decades of existence. He lived alone and loved the birds. Mostly, he loved the land and the magnitude of its feigned silence that spoke in so many voices, if one but slowed down enough to listen. Later that year I would decide to walk the Appalachian trail, my first multi-day hike of any distance.

That day we counted American Dippers, Winter and Marsh Wrens, numerous species of waterfowl, brightly plumed Stellar Jays, greyish Canada Jays, finches of all types, sparrows, chickadees and song birds, methodic woodpeckers and the carnivorous, crimson-tinged Northern Flickers.

That day I learned their names. That day, I heard their call, but until that day, I had not noticed that they were there all along. I simply hadn’t looked.

Joe Harkness knows this well. Bird watching, for him, was a way towards being more mindful, about establishing a connection to himself through the birds. It opened up my eyes, he says, to what I was doing when I was outside and at this point I started bird watching and it all sort of clicked into place and it became my therapy, my bird therapy. Harkness went on to blog about his experience and eventually published Bird Therapy: On The Healing Effects of Watching Birds. He watched birds and wrote his way towards reestablishing a connection to himself through the natural world from a very bleak place. You can listen to him speak about his experiences here.

GrrlScientist the science writer and ornithologist who profiled Harkness for Forbes Magazine agrees. She writes:

Although I’m a lifelong birder, I was particularly interested to learn how birding develops mindfulness. Birding is a meditative practice that immediately appeals to all your senses listening to bird sounds and songs, looking at their plumage colors and patterns, observing their complex and often subtle behaviors, identifying their habits and habitats but weirdly, I’d not made this connection between birding and mindfulness before.

In the past seven years, I had to slow down intentionally. With each step, I get slower, but somehow always find myself farther along. I am learning to carry the weight of childhood trauma: of war, of dislocation, of growing up, of being a conscientious member of the human species on this planet. I cannot say that it gets lighter but I am constantly learning myself against the context of the land and the contested places I occupy and share with other beings. I have come to find my stillness in movement.

Over the course of this Autumn, the eagles have been patrolling the river, hoping for spent and tired salmon swimming against the current. Each morning I wake up, look out the window and I see the eagle, sitting, waiting, hoping. I try to emulate her, push my ears out to listen to her shrill calls; imperceptible at first, camouflaged within the ambient noise and the chatter in my head--Then I hear it, make out her high pitched giggle: it is barely a whimper, sweet and melodic; and delightfully at odds with such a powerful creature.

I observe her stillness closely, tune my ears a bit sharper. I realize again that the eagle is teaching me something.

But it isn’t the eagle, not really. It is me. I am the stillness and the stillness is in me.

To Hope:

The salmon have moved on,

Having met, mated, given, and given up life;

Leaves on the Apple cling on,

though the birch is bare: tendrils in mist, asking questions, ashen white.

The bears too have gone to dream, dreaming their wintry dreams.

Yet she, sharp-eyed and whiteplumed,

Returns to this tree--her stalwart cottonwood.

Day after day,

Year after year.

Resources:

Crisis Centers Canada

USA Crisis Helplines

Bird songs and Calls of New Zealand

Cornell Lab of Ornithology (North American Bird Song registry)

Suggested Readings:

Wagamese, Richard. Medicine Walk , Starlight

Rorher, Finlo : Slow Death of Purposeless Walking

Harkness, Joe: Bird Therapy: On the Healing Effects of Watching Birds

Adams, Jill.U : How to Boost Your Empathy and Mindfulness While Birding

Birding With Benefits: How Nature Improves Our Mental Mindsets

Mock, Jillian : Black Birders Week Promotes Diversity and Takes on Racism in the Outdoors

Langin, Katie: ‘I can’t even enjoy this:’ #BlackBirdersWeek Organizer Shares Her Struggles

.png)