8 Tips for Backcountry Desert Hiking

8 Tips for Backcountry Desert Hiking

8 Tips for Backcountry Desert Hiking

YouTube video highlight

I’ve thru-hiked the Arizona Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail and the New Mexico portion of the Continental Divide Trail.

Read more about the projectThis fall, I thru-hiked the Hayduke Trail, a famously challenging 800 mile route through Utah and Arizona. Not only is the terrain challenging, but logistics and weather are especially dangerous and notoriously unpredictable.

I came into this experience with significant desert hiking experience. I’ve thru-hiked the Arizona Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail and the New Mexico portion of the Continental Divide Trail. None of these hikes compared to the intense bushwhacking, wayfinding, and cliff and boulder navigation I encountered on the Hayduke.

Below are eight crucial pieces of advice born from hiking for 38 days on the Hayduke Trail.

Navigating cliffs: “Measure twice, cut once”

Some sections require you to ascend or descend a cliff, canyon or other rocky feature. Stop before any major feature to plan out the safest route. For example, you not only need to be able to descend a cliff, but you also need to know how to get back up that cliff safely in case anything goes wrong. Sometimes you might drop down a cliff ledge only to find the next ledge has a drop that would be deadly and no safe alternatives except for climbing back up. Better to take a long alternate that keeps you safe than to risk a situation you can’t get yourself out of.

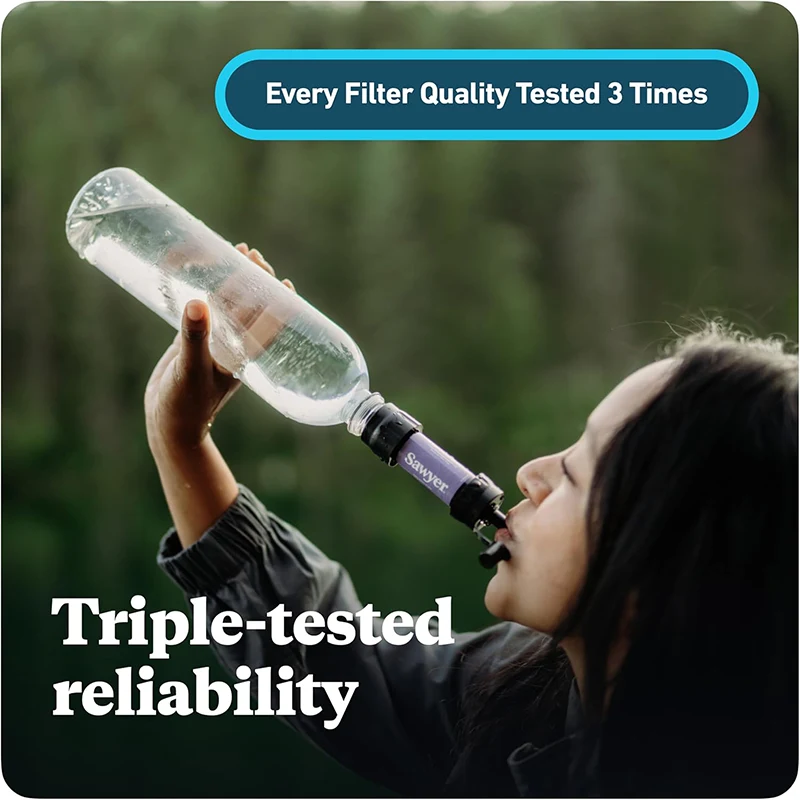

With water, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush

Water is a rare and precious resource, but having *no* water in the desert isn’t an option so it’s critical to take water collection and consumption seriously. You may only come across one water source (or none) on any given day. If you aren’t 100% certain that you have a better water source easily accessible ahead of you, then take whatever water you find if there’s a chance you will run out. During my hike that meant collecting slightly alkaline water, or muddy puddle water in a pinch. If you have access to clean water leave the nasty filter-clogging water in your filter bottle and don’t filter it until unless you have to. This prevents unnecessary clogging.

Neutralize alkaline water

Alkaline water is essentially salt water. It’s gross to drink and heavily alkaline water will actually make you thirstier in the long run if you drink it. It’s not “refreshing” and can feel heavy in your stomach.

You can guess if water will be alkaline based on if you find white salt crust on the rocks around the water source. It’s not guaranteed this will be the case, but I found it to be true nearly everywhere.

Never drink highly alkaline water. If you have to drink slightly alkaline water, try adding Mio or a powdered drink mix. These products are mostly citric acid which will neutralize the pH levels of the water, making it more palatable and refreshing To be clear, I’m not a scientist. I don’t know if doing this will actually hydrate you better, but it seemed to help in my anecdotal experience.

Take a Siesta

Depending on the time of year you’re hiking, it’s likely at some point you’ll need to take a siesta to avoid midday heat and sun exposure. The desert is often fully exposed and the heat builds up in the rocks that compounds throughout the day culminating in mid to late afternoon. I found myself taking a 45 minute break most days the first few weeks on trail in October. I used this time to rest, eat food and drink electrolytes, or distract from the heat with an episode of Friday Night Lights lol. This time to recharge is crucial to the sustainability of your hike on an exhausting trail like the Hayduke.

Don’t Trust Random Footprints

This may seem obvious… but it’s not. When you are bushwhacking for miles on end, if you find a set of another hiker’s footprints that seem to be going the same way as you, you’re going to be tempted to at least partially rely on them so you don’t have to go back to your maps/GPS as often. Don’t do it. You don’t know if their destination is the same as the one you are taking. I made this mistake a couple times on the Hayduke and it was a huge bummer and drain on resources having to backtrack.

Hand check the stability of rock before climbing

Dirt-rock, crumbly sandstone, and loose shale are abundant in the desert backcountry. On the Hayduke, I found myself climbing up or down unstable features for days. If I didn’t check my footing and grip before attempting scrambles and climbs, I could have fallen and gotten hurt. Even if it looks stable, take a second to tug on your handhold before you gamble by putting the weight of yourself (and your pack) on the hold.

Know how to spot/handle quicksand

You’ve probably heard of or seen quicksand in movies before, but here’s a video explaining what it actually is: What is Quicksand ? Does it really swallow people alive?

Quicksand isn’t deadly in and of itself but it can be an issue that slows you down and costs you valuable energy. Quicksand looks like solid, albeit wet, sand, but it acts more like a liquid. You might encounter it in washes and along rivers. Your legs will sink quickly into quicksand if you don’t rapidly and forcefully pull your legs upward repeatedly until you have gotten past the patch of quicksand. You won’t sink past your waist as the buoyancy of your lungs will keep you from sinking further but the deeper you sink the harder it can be to get out. Don’t panic and concentrate your energy on pulling your legs straight up and out of the quicksand and try not to lose your shoe!

Check flash flood conditions

The ground in the desert is typically rock or hard packed sand so it doesn’t absorb water quickly when it rains and this can cause flash flooding. If you’re in a more open area get to high ground and avoid channels of water that could sweep you off your feet. Find a dry overhang to hunker down under and wait it out.

If you find yourself in a canyon or in a narrow wash, get yourself out as quickly as possible. Rain water can quickly become a raging rapid in narrow canyons, especially slot canyons. If for some reason you are caught off guard and can’t get out in time, your best bet is to try to climb upwards and find a ledge to wait it out on but take precautions to avoid that scenario at all costs. Check the weather in advance and if you see a storm rolling in as you’re heading into a narrow canyon, set up camp and wait it out to make sure things are safe before continuing.

8 Tips for Backcountry Desert Hiking

This fall, I thru-hiked the Hayduke Trail, a famously challenging 800 mile route through Utah and Arizona. Not only is the terrain challenging, but logistics and weather are especially dangerous and notoriously unpredictable.

I came into this experience with significant desert hiking experience. I’ve thru-hiked the Arizona Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail and the New Mexico portion of the Continental Divide Trail. None of these hikes compared to the intense bushwhacking, wayfinding, and cliff and boulder navigation I encountered on the Hayduke.

Below are eight crucial pieces of advice born from hiking for 38 days on the Hayduke Trail.

Navigating cliffs: “Measure twice, cut once”

Some sections require you to ascend or descend a cliff, canyon or other rocky feature. Stop before any major feature to plan out the safest route. For example, you not only need to be able to descend a cliff, but you also need to know how to get back up that cliff safely in case anything goes wrong. Sometimes you might drop down a cliff ledge only to find the next ledge has a drop that would be deadly and no safe alternatives except for climbing back up. Better to take a long alternate that keeps you safe than to risk a situation you can’t get yourself out of.

With water, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush

Water is a rare and precious resource, but having *no* water in the desert isn’t an option so it’s critical to take water collection and consumption seriously. You may only come across one water source (or none) on any given day. If you aren’t 100% certain that you have a better water source easily accessible ahead of you, then take whatever water you find if there’s a chance you will run out. During my hike that meant collecting slightly alkaline water, or muddy puddle water in a pinch. If you have access to clean water leave the nasty filter-clogging water in your filter bottle and don’t filter it until unless you have to. This prevents unnecessary clogging.

Neutralize alkaline water

Alkaline water is essentially salt water. It’s gross to drink and heavily alkaline water will actually make you thirstier in the long run if you drink it. It’s not “refreshing” and can feel heavy in your stomach.

You can guess if water will be alkaline based on if you find white salt crust on the rocks around the water source. It’s not guaranteed this will be the case, but I found it to be true nearly everywhere.

Never drink highly alkaline water. If you have to drink slightly alkaline water, try adding Mio or a powdered drink mix. These products are mostly citric acid which will neutralize the pH levels of the water, making it more palatable and refreshing To be clear, I’m not a scientist. I don’t know if doing this will actually hydrate you better, but it seemed to help in my anecdotal experience.

Take a Siesta

Depending on the time of year you’re hiking, it’s likely at some point you’ll need to take a siesta to avoid midday heat and sun exposure. The desert is often fully exposed and the heat builds up in the rocks that compounds throughout the day culminating in mid to late afternoon. I found myself taking a 45 minute break most days the first few weeks on trail in October. I used this time to rest, eat food and drink electrolytes, or distract from the heat with an episode of Friday Night Lights lol. This time to recharge is crucial to the sustainability of your hike on an exhausting trail like the Hayduke.

Don’t Trust Random Footprints

This may seem obvious… but it’s not. When you are bushwhacking for miles on end, if you find a set of another hiker’s footprints that seem to be going the same way as you, you’re going to be tempted to at least partially rely on them so you don’t have to go back to your maps/GPS as often. Don’t do it. You don’t know if their destination is the same as the one you are taking. I made this mistake a couple times on the Hayduke and it was a huge bummer and drain on resources having to backtrack.

Hand check the stability of rock before climbing

Dirt-rock, crumbly sandstone, and loose shale are abundant in the desert backcountry. On the Hayduke, I found myself climbing up or down unstable features for days. If I didn’t check my footing and grip before attempting scrambles and climbs, I could have fallen and gotten hurt. Even if it looks stable, take a second to tug on your handhold before you gamble by putting the weight of yourself (and your pack) on the hold.

Know how to spot/handle quicksand

You’ve probably heard of or seen quicksand in movies before, but here’s a video explaining what it actually is: What is Quicksand ? Does it really swallow people alive?

Quicksand isn’t deadly in and of itself but it can be an issue that slows you down and costs you valuable energy. Quicksand looks like solid, albeit wet, sand, but it acts more like a liquid. You might encounter it in washes and along rivers. Your legs will sink quickly into quicksand if you don’t rapidly and forcefully pull your legs upward repeatedly until you have gotten past the patch of quicksand. You won’t sink past your waist as the buoyancy of your lungs will keep you from sinking further but the deeper you sink the harder it can be to get out. Don’t panic and concentrate your energy on pulling your legs straight up and out of the quicksand and try not to lose your shoe!

Check flash flood conditions

The ground in the desert is typically rock or hard packed sand so it doesn’t absorb water quickly when it rains and this can cause flash flooding. If you’re in a more open area get to high ground and avoid channels of water that could sweep you off your feet. Find a dry overhang to hunker down under and wait it out.

If you find yourself in a canyon or in a narrow wash, get yourself out as quickly as possible. Rain water can quickly become a raging rapid in narrow canyons, especially slot canyons. If for some reason you are caught off guard and can’t get out in time, your best bet is to try to climb upwards and find a ledge to wait it out on but take precautions to avoid that scenario at all costs. Check the weather in advance and if you see a storm rolling in as you’re heading into a narrow canyon, set up camp and wait it out to make sure things are safe before continuing.

8 Tips for Backcountry Desert Hiking

This fall, I thru-hiked the Hayduke Trail, a famously challenging 800 mile route through Utah and Arizona. Not only is the terrain challenging, but logistics and weather are especially dangerous and notoriously unpredictable.

I came into this experience with significant desert hiking experience. I’ve thru-hiked the Arizona Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail and the New Mexico portion of the Continental Divide Trail. None of these hikes compared to the intense bushwhacking, wayfinding, and cliff and boulder navigation I encountered on the Hayduke.

Below are eight crucial pieces of advice born from hiking for 38 days on the Hayduke Trail.

Navigating cliffs: “Measure twice, cut once”

Some sections require you to ascend or descend a cliff, canyon or other rocky feature. Stop before any major feature to plan out the safest route. For example, you not only need to be able to descend a cliff, but you also need to know how to get back up that cliff safely in case anything goes wrong. Sometimes you might drop down a cliff ledge only to find the next ledge has a drop that would be deadly and no safe alternatives except for climbing back up. Better to take a long alternate that keeps you safe than to risk a situation you can’t get yourself out of.

With water, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush

Water is a rare and precious resource, but having *no* water in the desert isn’t an option so it’s critical to take water collection and consumption seriously. You may only come across one water source (or none) on any given day. If you aren’t 100% certain that you have a better water source easily accessible ahead of you, then take whatever water you find if there’s a chance you will run out. During my hike that meant collecting slightly alkaline water, or muddy puddle water in a pinch. If you have access to clean water leave the nasty filter-clogging water in your filter bottle and don’t filter it until unless you have to. This prevents unnecessary clogging.

Neutralize alkaline water

Alkaline water is essentially salt water. It’s gross to drink and heavily alkaline water will actually make you thirstier in the long run if you drink it. It’s not “refreshing” and can feel heavy in your stomach.

You can guess if water will be alkaline based on if you find white salt crust on the rocks around the water source. It’s not guaranteed this will be the case, but I found it to be true nearly everywhere.

Never drink highly alkaline water. If you have to drink slightly alkaline water, try adding Mio or a powdered drink mix. These products are mostly citric acid which will neutralize the pH levels of the water, making it more palatable and refreshing To be clear, I’m not a scientist. I don’t know if doing this will actually hydrate you better, but it seemed to help in my anecdotal experience.

Take a Siesta

Depending on the time of year you’re hiking, it’s likely at some point you’ll need to take a siesta to avoid midday heat and sun exposure. The desert is often fully exposed and the heat builds up in the rocks that compounds throughout the day culminating in mid to late afternoon. I found myself taking a 45 minute break most days the first few weeks on trail in October. I used this time to rest, eat food and drink electrolytes, or distract from the heat with an episode of Friday Night Lights lol. This time to recharge is crucial to the sustainability of your hike on an exhausting trail like the Hayduke.

Don’t Trust Random Footprints

This may seem obvious… but it’s not. When you are bushwhacking for miles on end, if you find a set of another hiker’s footprints that seem to be going the same way as you, you’re going to be tempted to at least partially rely on them so you don’t have to go back to your maps/GPS as often. Don’t do it. You don’t know if their destination is the same as the one you are taking. I made this mistake a couple times on the Hayduke and it was a huge bummer and drain on resources having to backtrack.

Hand check the stability of rock before climbing

Dirt-rock, crumbly sandstone, and loose shale are abundant in the desert backcountry. On the Hayduke, I found myself climbing up or down unstable features for days. If I didn’t check my footing and grip before attempting scrambles and climbs, I could have fallen and gotten hurt. Even if it looks stable, take a second to tug on your handhold before you gamble by putting the weight of yourself (and your pack) on the hold.

Know how to spot/handle quicksand

You’ve probably heard of or seen quicksand in movies before, but here’s a video explaining what it actually is: What is Quicksand ? Does it really swallow people alive?

Quicksand isn’t deadly in and of itself but it can be an issue that slows you down and costs you valuable energy. Quicksand looks like solid, albeit wet, sand, but it acts more like a liquid. You might encounter it in washes and along rivers. Your legs will sink quickly into quicksand if you don’t rapidly and forcefully pull your legs upward repeatedly until you have gotten past the patch of quicksand. You won’t sink past your waist as the buoyancy of your lungs will keep you from sinking further but the deeper you sink the harder it can be to get out. Don’t panic and concentrate your energy on pulling your legs straight up and out of the quicksand and try not to lose your shoe!

Check flash flood conditions

The ground in the desert is typically rock or hard packed sand so it doesn’t absorb water quickly when it rains and this can cause flash flooding. If you’re in a more open area get to high ground and avoid channels of water that could sweep you off your feet. Find a dry overhang to hunker down under and wait it out.

If you find yourself in a canyon or in a narrow wash, get yourself out as quickly as possible. Rain water can quickly become a raging rapid in narrow canyons, especially slot canyons. If for some reason you are caught off guard and can’t get out in time, your best bet is to try to climb upwards and find a ledge to wait it out on but take precautions to avoid that scenario at all costs. Check the weather in advance and if you see a storm rolling in as you’re heading into a narrow canyon, set up camp and wait it out to make sure things are safe before continuing.